When Is an Asteroid Not an Asteroid?

On March 29, 1807, German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers spotted Vesta as a moving pinprick of light in the sky. Two hundred and four years later, as NASA’s Dawn spacecraft prepares to begin orbiting this intriguing world, scientists now know how special this object is, even if there has been some debate on how to classify it.

Vesta is most commonly called an asteroid because it lies in the orbiting rubble patch known as the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. But the vast majority of objects in the main belt are lightweights, about 60 miles wide, while Vesta is 330 miles across on average.

“I don’t think Vesta should be called an asteroid,” said Tom McCord, a Dawn co-investigator based at the Bear Fight Institute, Winthrop, Wash. “Not only is Vesta so much larger, but it’s an evolved object, unlike most things we call asteroids.”

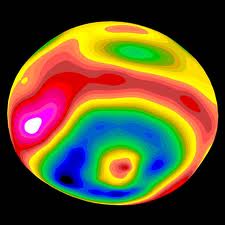

The layered structure of Vesta (core, mantle and crust) is the key trait that makes Vesta more like planets such as Earth, Venus, and Mars than like the other asteroids, McCord said. Like the planets, Vesta had sufficient radioactive material inside when it coalesced, releasing heat that melted rock and enabled lighter layers to float to the outside. Scientists call this process differentiation.

McCord and colleagues were the first to discover that Vesta was likely differentiated when special detectors on their telescopes in 1972 picked up the signature of basalt, a rock associated with volcanic activity. That meant that the body had to have melted at one time.

Officially, Vesta is a “minor planet”—a body that orbits the Sun but is not a proper planet or comet. But there are more than 540,000 minor planets in our solar system, so the label doesn’t give Vesta much distinction. Dwarf planets—which include Dawn’s second destination, Ceres—are another category, but Vesta doesn’t qualify as one of those. For one thing, Vesta isn’t quite large enough.

Dawn scientists prefer to think of Vesta as a protoplanet because it is a dense, layered body that orbits the Sun and began in the same fashion as Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars, but somehow never fully developed. In the swinging early history of the solar system, objects became planets by merging with other Vesta-sized objects. But Vesta never found a partner during that big dance, and the critical time passed. It may have had to do with the nearby presence of Jupiter, the neighborhood’s gravitational superpower, disturbing the orbits of objects and hogging the dance partners.

Other space rocks have collided with Vesta and knocked off bits of it. Those became debris in the asteroid belt known as Vestoids, and even hundreds of meteorites that have ended up on Earth. But Vesta never collided with something of sufficient size to disrupt it, and it remained intact. As a result, Vesta is a time capsule from that earlier era.

“This gritty little protoplanet has survived bombardment in the asteroid belt for over 4.5 billion years, making its surface possibly the oldest planetary surface in the solar system,” said Christopher Russell, Dawn’s principal investigator, based at UCLA. “Studying Vesta will enable us to write a much better history of the solar system’s turbulent youth.”

“Dawn’s ion thrusters are gently carrying us toward Vesta, and the spacecraft is getting ready for its big year of exploration,” added Marc Rayman, Dawn’s chief engineer at JPL.

You can contact Bob Eklund at [email protected], or visit his websites at www.bobeklund.com and http://www.firststarbook.com.

Be the first to comment