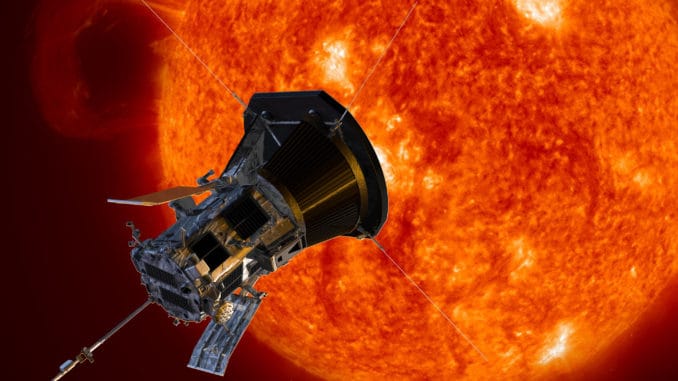

When NASA’s Parker Solar Probe launches into space from the Kennedy Space Center August 11, it will begin its journey to the Sun, our nearest star. The Parker Solar Probe will travel almost 90 million miles and eventually enter through the Sun’s outer atmosphere to encounter a dangerous environment of intense heat and solar radiation. During this harrowing journey, it will fly closer to the Sun than any other human-made object.

To revolutionize our understanding of our most important and life-sustaining star, scientists and engineers have built a suite of instruments aboard the Parker Solar Probe to conduct different experiments. Some of these instruments will be protected by a thick carbon-composite heat shield. However, others will be more exposed.

The Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons (SWEAP) investigation is the set of instruments that will directly measure the hot ionized gas in the solar atmosphere during the solar encounters. A key instrument on SWEAP called the Solar Probe Cup (SPC) was built at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) in Cambridge, Mass.

The SPC is a small metal device that will peer around the protective heat shield of the spacecraft directly at the Sun. It will face some of the most extreme conditions ever encountered by a scientific instrument, and allow a sample of the Sun’s atmosphere to be swept up for the first time.

The SPC uses high voltages to determine what type of particles can enter, which is a way of measuring the energy of the particle. This is crucial information for probing the wind of hot ionized gas that is constantly produced by the Sun. As the spacecraft flies towards the Sun for an encounter, the wind is directed straight into the cup.

This unique probe of the solar wind is important for scientists to better understand space weather, which is responsible for effects that range from endangering astronauts on space walks to impacting the electronics in communications satellites.

The solar probe will travel faster than any spacecraft in history, at its peak reaching 430,000 miles per hour, and will be only four-and-a-half solar diameters, or 3.8 million miles, above the solar surface at its closet approach to the Sun around 2024. The probe is equipped with a heat shield to protect its sensors from the Sun’s heat, which could reach 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit, nearly hot enough to melt steel.

At this distance, the solar probe will be within a region where electrons and ionized atoms—mostly hydrogen ions, or protons, and helium ions, called alpha particles—are accelerated and shot out toward the planets at high speed.

When these ions, called the solar wind, hit Earth, they interact with Earth’s magnetic fields and generate the northern and southern lights as well as storms in the outermost atmosphere that interfere with radio communications and satellite operations. Accelerated to higher speeds, so-called “solar energetic” particles can pose a hazard to astronauts.

The namesake of the mission is a Caltech alumnus, 91-year-old Eugene Parker (PhD ‘51), who predicted, in 1958, the existence of a supersonic solar wind—a flow of charged particles that stream off the Sun, accelerating at speeds faster than that of sound.

Be the first to comment