Arizona State University astronomer Adam Schneider and his colleagues are hunting for an elusive object lost in space between our Sun and the nearest stars. They are asking for your help in the search, using a new citizen-science website.

Arizona State University astronomer Adam Schneider and his colleagues are hunting for an elusive object lost in space between our Sun and the nearest stars. They are asking for your help in the search, using a new citizen-science website.

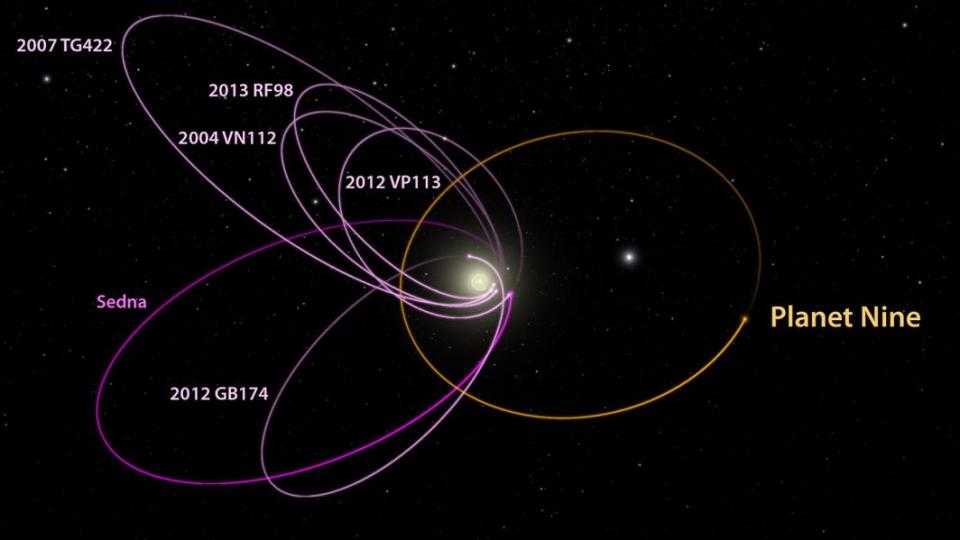

Astronomers have found evidence for a ninth planet in our solar system. The evidence comes from studying the orbits of objects in the solar system’s Kuiper Belt. This is a zone of comet-like bodies orbiting the Sun out beyond the orbit of Neptune. The Kuiper Belt is similar to the asteroid belt that circles the Sun between Mars and Jupiter, but it lies dozens of times farther out.

This hypothetical Planet 9 could be similar in size to Neptune, but it may orbit up to a thousand times farther away from the Sun than the Earth does. So while astronomers can see its effects on the Kuiper Belt objects, no one has yet observed Planet 9 directly.

“If it exists, Planet 9 could be large—maybe 10 times the mass of Earth but orbiting far out beyond the Kuiper Belt,” says Schneider, a postdoctoral researcher in ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

In addition to searching for a distant planet orbiting the Sun, this new project will help astronomers identify the Sun’s nearest neighbors outside of our solar system.

“There are just over four light-years between Neptune and Proxima Centauri, the nearest star, and much of this vast territory is unexplored,” says the lead researcher for Backyard Worlds: Planet 9, Marc Kuchner, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

Astronomers expect the Sun’s neighborhood will contain many low-mass objects called brown dwarfs. These emit very little light at visible wavelengths, but instead glow dimly with infrared—i.e., heat—radiation.

So how do astronomers find such objects in space? That’s where you can contribute, using a website that enlists the help of citizen scientists. It’s called Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 [http://backyardworlds.org], and it uses images taken by NASA’s WISE space telescope.

WISE, which stands for Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, was launched in late 2009, and it has mapped the entire sky several times during the last seven years. WISE detects infrared light, the kind of light emitted by objects at room temperature, like planets and brown dwarfs. This sensitivity to infrared light makes WISE uniquely suited for discovering Planet 9, if it exists.

But there’s a snag: Images from WISE have captured nearly 750 million individual sources in the sky. Doubtlessly among these lurk the elusive brown dwarfs and possibly Planet 9. The question is how to sift through the data and identify them.

The trick to finding these needles in haystacks of WISE data is to look for something in motion. Planetary objects and brown dwarfs roaming near the Sun can appear to move across the sky, leaving other celestial objects such as background stars and galaxies, which lie immensely far away, apparently fixed in place.

So the best hope for discovering these worlds is to systematically scan infrared images of the sky, searching for objects that move.

Automated searches for moving objects in the WISE data have already proven successful, but computerized searches are often overwhelmed by image artifacts—visual noise—especially in crowded parts of the sky.

As Schneider explains, “People who join in the Backyard Worlds search bring a unique skill to the search: the human ability to recognize movement.”

For instructions on joining the program, see the Backyard Worlds website, backyardworlds.org

Be the first to comment