Mars scientists are wrestling with a problem. Ample evidence says ancient Mars was sometimes wet, with water flowing and pooling on the planet’s surface. Yet the ancient Sun was about one-third less warm, and climate modelers struggle to produce scenarios that get the surface of Mars warm enough for keeping water unfrozen.

Mars scientists are wrestling with a problem. Ample evidence says ancient Mars was sometimes wet, with water flowing and pooling on the planet’s surface. Yet the ancient Sun was about one-third less warm, and climate modelers struggle to produce scenarios that get the surface of Mars warm enough for keeping water unfrozen.

A leading theory is to have a thicker carbon-dioxide atmosphere forming a greenhouse-gas blanket, helping to warm the surface of ancient Mars. However, according to a new analysis of data from NASA’s Mars rover Curiosity, Mars had far too little carbon dioxide about 3.5 billion years ago to provide enough greenhouse-effect warming to thaw water ice.

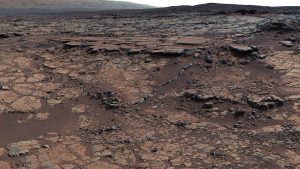

The same Martian bedrock in which Curiosity found sediments from an ancient lake where microbes could have thrived is the source of the evidence adding to the quandary about how such a lake could have existed. Curiosity detected no carbonate minerals in the samples of the bedrock it analyzed. The new analysis concludes that the dearth of carbonates in that bedrock means Mars’ atmosphere when the lake existed could not have held much carbon dioxide.

“We’ve been particularly struck with the absence of carbonate minerals in sedimentary rock the rover has examined,” said Thomas Bristow of NASA’s Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, California. “It would be really hard to get liquid water even if there were a hundred times more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than what the mineral evidence in the rock tells us.” Bristow is the principal investigator for the Chemistry and Mineralogy (CheMin) instrument on Curiosity and lead author of the study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Curiosity has made no definitive detection of carbonates in any lakebed rocks sampled since it landed in Gale Crater in 2011. CheMin can identify carbonate if it makes up just a few percent of the rock.

For the past two decades, researchers have used spectrometers on Mars orbiters to search for carbonate that could have resulted from an early era of more abundant carbon dioxide. They have found far less than anticipated.

“It’s been a mystery why there hasn’t been much carbonate seen from orbit,” Bristow said. “You could get out of the quandary by saying the carbonates may still be there, but we just can’t see them from orbit because they’re covered by dust, or buried, or we’re not looking in the right place. The Curiosity results bring the paradox to a focus. This is the first time we’ve checked for carbonates on the ground in a rock we know formed from sediments deposited under water.”

The new analysis concludes that no more than a few tens of millibars of carbon dioxide could have been present when the lake existed, or it would have produced enough carbonate for Curiosity’s CheMin to detect it. A millibar is one one-thousandth of sea-level air pressure on Earth. The current atmosphere of Mars is less than 10 millibars and about 95 percent carbon dioxide.

“This analysis fits with many theoretical studies that the surface of Mars, even that long ago, was not warm enough for water to be liquid,” said Robert Haberle, a Mars-climate scientist at NASA Ames and a co-author of the paper. “It’s really a puzzle to me.”

When two lines of scientific evidence appear irreconcilable, the scene may be set for an advance in understanding why they don’t agree. Curiosity is continuing to investigate ancient environmental conditions on Mars.

Be the first to comment