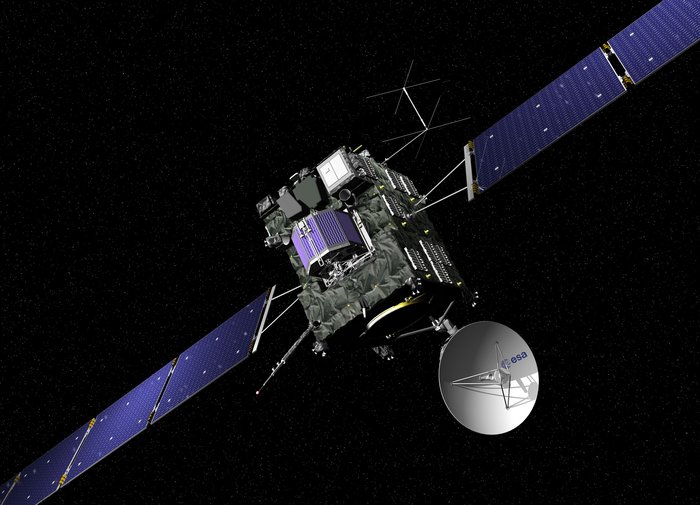

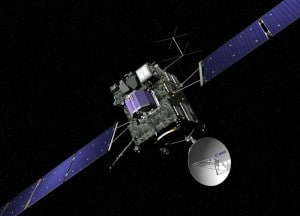

With the Philae lander’s mission complete, Rosetta will now continue its own extraordinary exploration, orbiting Comet 67P/Churymov–Gerasimenko during the coming year as the enigmatic body arcs ever closer to our Sun.

With the Philae lander’s mission complete, Rosetta will now continue its own extraordinary exploration, orbiting Comet 67P/Churymov–Gerasimenko during the coming year as the enigmatic body arcs ever closer to our Sun.

Last week, ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft delivered its Philae lander to the surface of the comet for a dramatic touchdown. The lander’s planned mission ended after about 64 hours when its batteries ran out, but not before it delivered a full set of results that are now being analyzed by scientists across Europe.

Rosetta’s own mission is far from over and the spacecraft remains in excellent condition, with all of its systems and instruments performing as expected.

“With lander delivery complete, Rosetta will resume routine science observations and we will transition to the ‘comet escort phase’,” says Flight Director Andrea Accomazzo. “This science-gathering phase will take us into next year as we go with the comet towards the Sun, passing perihelion, or closest approach, on 13 August, at 186 million kilometres from our star.”

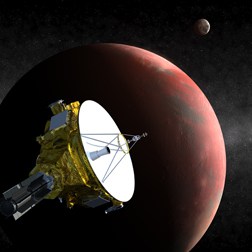

WAKEUP CALL FOR NEW HORIZONS. NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft will come out of  hibernation for the last time on Dec. 6. Between now and then, while the Pluto-bound probe enjoys three more weeks of electronic slumber, work on Earth is well under way to prepare the spacecraft for a six-month encounter with the dwarf planet that begins in January.

hibernation for the last time on Dec. 6. Between now and then, while the Pluto-bound probe enjoys three more weeks of electronic slumber, work on Earth is well under way to prepare the spacecraft for a six-month encounter with the dwarf planet that begins in January.

“New Horizons is healthy and cruising quietly through deep space—nearly three billion miles from home—but its rest is nearly over,” says Alice Bowman, New Horizons mission operations manager at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Md. “It’s time for New Horizons to wake up, get to work, and start making history.”

Since launching in January 2006, New Horizons has spent 1,873 days in hibernation—about two-thirds of its flight time—spread over 18 separate hibernation periods from mid-2007 to late 2014 that ranged from 36 days to 202 days long.

In hibernation mode much of the spacecraft is unpowered; the onboard flight computer monitors system health and broadcasts a weekly beacon-status tone back to Earth. On average, operators woke New Horizons just over twice each year to check out critical systems, calibrate instruments, gather science data, rehearse Pluto-encounter activities and perform course corrections when necessary.

New Horizons pioneered routine cruise-flight hibernation for NASA. Not only has hibernation reduced wear and tear on the spacecraft’s electronics, it lowered operations costs and freed up NASA Deep Space Network tracking and communication resources for other missions.

Tops on the mission’s science list are characterizing the global geology and topography of Pluto and its large moon Charon, mapping their surface compositions and temperatures, examining Pluto’s atmospheric composition and structure, studying Pluto’s smaller moons and searching for new moons and rings.

New Horizons’ seven-instrument science payload includes advanced imaging infrared and ultraviolet spectrometers, a compact multicolor camera, a high-resolution telescopic camera, two powerful particle spectrometers, a space-dust detector (designed and built by students at the University of Colorado) and two radio-science experiments. The entire spacecraft, drawing electricity from a single radioisotope thermoelectric generator, operates on less power than a pair of 100-watt light bulbs.

Distant observations of the Pluto system begin Jan. 15 and will continue until late July 2015; closest approach to Pluto is on July 14.

Photo credit – ESA, New Horizons

Be the first to comment