Imagine living on a planet that has two suns. One you orbit, and the other is a very bright, nearby neighbor looming large in your sky. With this “second sun” in the sky, nightfall might be a rare event, perhaps only coming seasonally to your planet. A new study suggests that this could be far more common than we realized.

Imagine living on a planet that has two suns. One you orbit, and the other is a very bright, nearby neighbor looming large in your sky. With this “second sun” in the sky, nightfall might be a rare event, perhaps only coming seasonally to your planet. A new study suggests that this could be far more common than we realized.

NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope has confirmed about 1,000 exoplanets. Until now, there has been an unanswered question about exoplanet host stars: how many host stars are binaries, or double stars? Binary stars have long been known to be commonplace—about half the stars in the sky are believed to consist of two stars orbiting each other. So, are stars with planets equally likely to have a companion star, or do companion stars prevent the formation of planets?

The study, by a team of astronomers led by Dr. Elliott Horch, Southern Connecticut State University, has shown that stars with exoplanets are just as likely to have a binary companion: 40% to 50% of the host stars of confirmed exoplanets are actually binary stars.

Their study makes use of very high spatial resolution observations that were carried out on the WIYN telescope located on Kitt Peak in southern Arizona and the Gemini North telescope located on Mauna Kea in Hawaii. The technique used by the team is called speckle imaging and consists of obtaining digital images (15 to 25 times a second) of a small portion of the sky surrounding a star of interest. The images are then combined in software using a complex set of algorithms, yielding a final picture of the star with a resolution better that that of the Hubble Space Telescope.

By using this technique, the team can detect companion stars that are up to 125 times fainter than the target but only 0.05 arcsecond away. For the majority of the Kepler stars, this means companion stars with a true separation of a few to about 100 times the Sun-Earth distance. By noting the occurrence rate of these true binary companion stars, the discoveries can be extended to show that half of the stars that host exoplanets are probably binaries.

Co-author of the study, Dr. Steve B. Howell (NASA Ames Research Center), commented, “An interesting consequence of this finding is that in the half of the exoplanet host stars that are binary we can not, in general, say which star in the system the planet actually orbits.”

The Kepler orbiting telescope has discovered a number of circumbinary planets, that is, a planet that orbits both stars in very close binary systems. There also exist exoplanets that are known to orbit one of the stars in very wide binary systems. If the two stars are very close to each other and the planet far away, a circumbinary planet will be reminiscent of the planet Tatooine in “Star Wars.” If instead the exoplanet orbits one of the stars in a very wide pair, the companion star might appear simply as a bright star among others in the night sky. “Somewhere there will be a transition between these two scenarios,” Howell said, “but we are far from knowing where.”

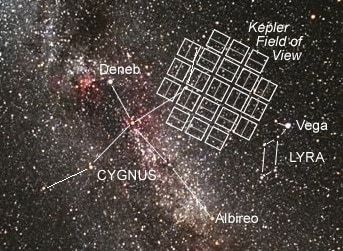

The accompanying figure marks out the Kepler Space Telescope’s field of view (the part of the sky being studied here), located between two bright stars in the “summer triangle,” rising over the Kitt Peak telescope in southern Arizona.

Be the first to comment