January 20, 2014: It was a fairy-tale ending to a tense chapter in the story of the Rosetta space mission, as the European Space Agency (ESA) heard from its distant spacecraft for the first time in 31 months.

January 20, 2014: It was a fairy-tale ending to a tense chapter in the story of the Rosetta space mission, as the European Space Agency (ESA) heard from its distant spacecraft for the first time in 31 months.

Launched in 2004, Rosetta is chasing down Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, where it will become the first space mission to rendezvous with a comet, the first to attempt a landing on a comet’s surface, and the first to follow a comet as it swings around the Sun.

Operating on solar energy alone, Rosetta was placed into a deep space slumber in June 2011 as it cruised out to a distance of nearly 800 million km from the warmth of the Sun, beyond the orbit of Jupiter. Now, as Rosetta’s orbit has brought it back to within ‘only’ 673 million km from the Sun, there is enough solar energy to power the spacecraft fully again.

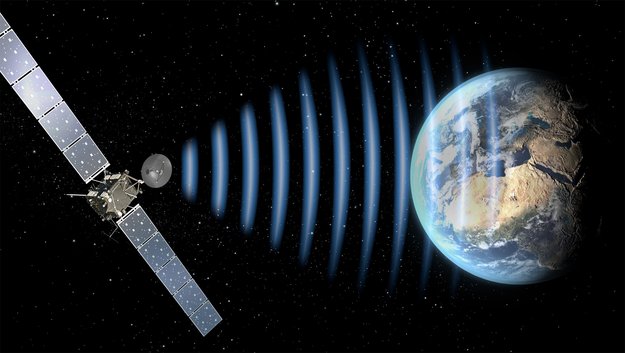

ROSETTA CALLS HOME

Thus on January 20, still about 9 million km from the comet, Rosetta’s pre-programmed internal ‘alarm clock’ woke up the spacecraft. After warming up its key navigation instruments, coming out of a stabilizing spin, and aiming its main radio antenna at Earth, Rosetta sent a signal to let mission operators know it had survived the most distant part of its journey.

The signal was received by both NASA’s Goldstone and Canberra ground stations during the first window of opportunity the spacecraft had to communicate with Earth, and the successful wake-up was announced via the @ESA_Rosetta twitter account, which tweeted: “Hello, World!”

Comets are considered the primitive building blocks of the Solar System and likely helped to ‘seed’ Earth with water, perhaps even the ingredients for life.

“All other comet missions have been flybys, capturing fleeting moments in the life of these icy treasure chests,” says Matt Taylor, ESA’s Rosetta project scientist. “With Rosetta, we will track the evolution of a comet on a daily basis and for over a year, giving us a unique insight into a comet’s behavior.”

After rendezvous this August, Rosetta will start with two months of mapping of the comet’s surface, and will also measure the comet’s gravity, mass and shape, and assess its gaseous, dust-laden atmosphere, or coma. Using these data, scientists will choose a landing site for the mission’s 100 kg Philae probe. The landing is currently scheduled for 11 November and will be the first time that a landing on a comet has ever been attempted.

In fact, given the almost negligible gravity of the comet’s 4 km-wide nucleus, Philae will have to use ice screws and harpoons to stop it from rebounding back into space after touchdown.

Among its wide range of scientific measurements, Philae will send back a panorama of its surroundings, as well as very high-resolution pictures of the surface. It will also perform an on-the-spot analysis of the composition of the ices and organic material, including drilling down to 23 cm below the surface and feeding samples to Philae’s on-board laboratory for analysis.

The focus of the mission will then move to the ‘escort’ phase, during which Rosetta will stay alongside the comet as it moves closer to the Sun, monitoring the ever-changing conditions on the surface as the comet warms up and its ices vaporize.

The comet will reach its closest distance to the Sun in August, 2015, at about 185 million km, roughly between the orbits of Earth and Mars. Rosetta will follow the comet throughout the remainder of 2015, as it heads away from the Sun.

Be the first to comment