Researchers from Texas A&M University and the University of Texas at Austin teamed up to detect the most distant galaxy ever found—one created only 700 million years after the Big Bang. Their research is published in the Oct. 24 edition of the journal Nature.

Researchers from Texas A&M University and the University of Texas at Austin teamed up to detect the most distant galaxy ever found—one created only 700 million years after the Big Bang. Their research is published in the Oct. 24 edition of the journal Nature.

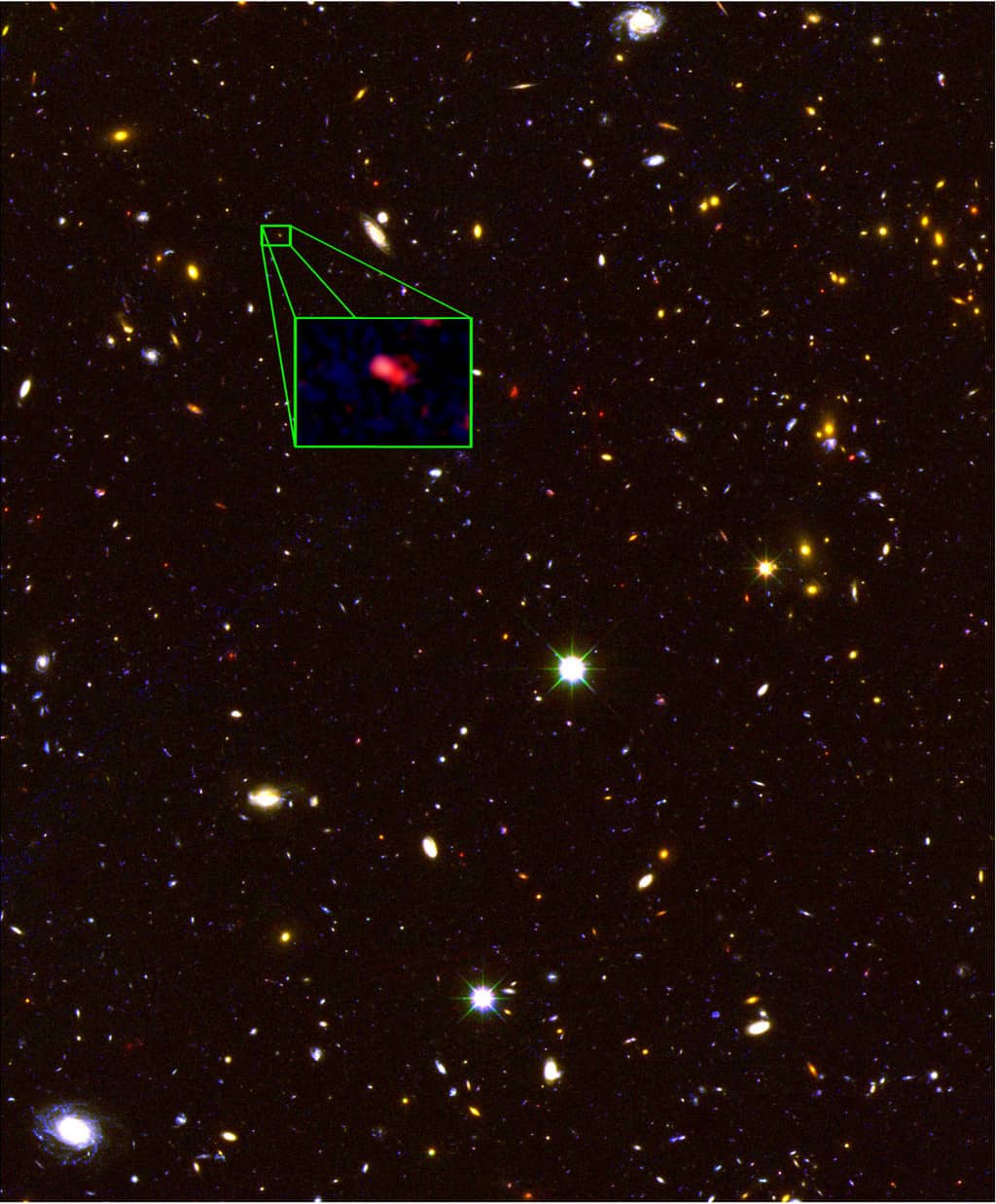

The galaxy, known by its catalog name z8_GND_5296, was observed as it was 13 billion years ago. That’s the time it took for the galaxy’s light to travel to Earth. Because the universe has been expanding all that time, the researchers estimate the galaxy’s present distance to be roughly 30 billion light-years from Earth.

“Because of its distance, we get a glimpse of conditions when the universe was only about 700 million years old—only 5 percent of its current age of 13.8 billion years,” said Texas A&M astrophysicist Casey Papovich, who is second author of the paper.

He explains that researchers are able to accurately gauge the distances of galaxies by measuring a feature from the ubiquitous element hydrogen called the Lyman alpha transition, which emits brightly in distant galaxies. It’s detected in nearly all galaxies that are seen from a time more than one billion years from the Big Bang, but getting closer than that, the hydrogen emission line, for some reason, becomes increasingly difficult to see.

“We were thrilled to see this galaxy,” said lead author is Steven Finkelstein, an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin “And then our next thought was, ‘Why did we not see anything else? We’re using the best instrument on the best telescope with the best galaxy sample. We had the best weather—it was gorgeous. And still, we only saw this emission line from one of our sample of 43 observed galaxies, when we expected to see around six. What’s going on?”

The researchers suspect they may have zeroed in on the era when the universe made its transition from an opaque state in which most of the hydrogen is neutral to a translucent state in which most of the hydrogen is ionized. So it’s not necessarily that the distant galaxies aren’t there—it could be that they’re hidden from detection behind a wall of neutral hydrogen fog, which blocks the hydrogen emission signal.

The Nature paper grew out of raw data gleaned from a powerful Hubble Space Telescope imaging survey of the distant universe Using that data, the team was armed with 43 potential distant galaxies and set out to confirm their distances.

On a crisp, clear April night, team members sat behind a panel of computers in the control room of the W. M. Keck Observatory, which is perched atop the 14,000-foot summit of Hawaii’s dormant Mauna Kea volcano and houses the two largest optical and infrared telescopes in the world, each standing eight stories tall, weighing 300 tons and equipped with 10-meter-wide mirrors.

They detected only one galaxy during their two nights of observation at Keck, but it turned out to be the most distant ever confirmed. It had a redshift of 7.51—indicating that it was created about 13 billion years ago. Because the universe is expanding, the space between galaxies also is increasing. And as objects move away from an observer, their light becomes redder. In essence, the higher the “redshift,” the farther away the object. Only five other galaxies have ever been confirmed to have a redshift greater than 7, with the previous high being 7.215.

Be the first to comment