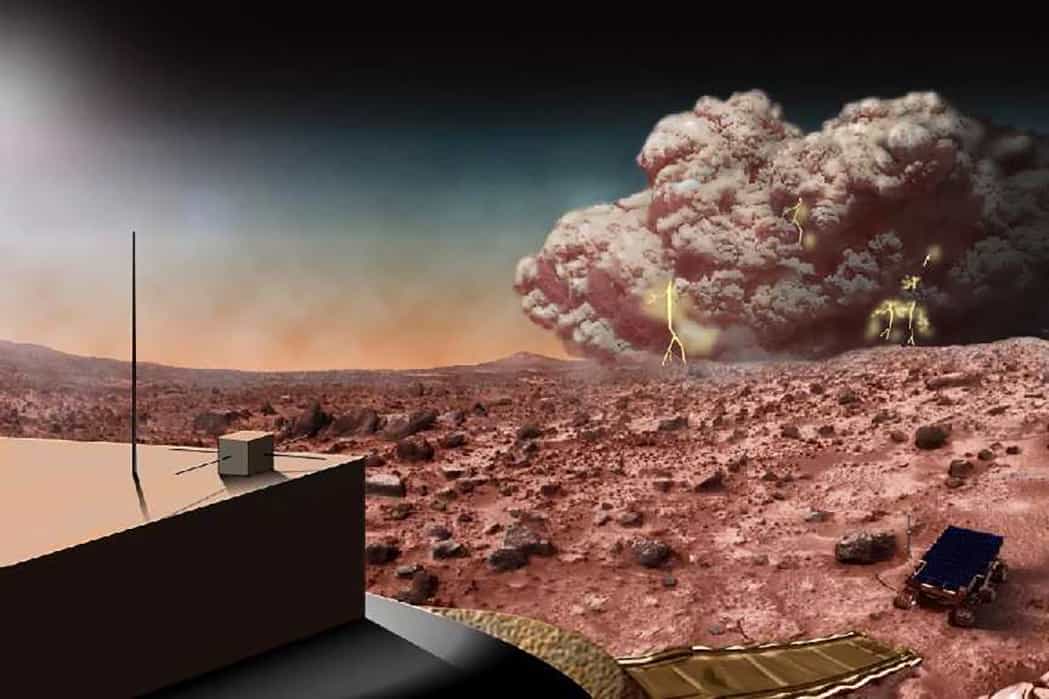

On Mars, wind rules. Wind has been shaping the Red Planet’s landscapes for billions of years and continues to do so today. Studies using both a NASA orbiter and a rover reveal its effects on scales grand to tiny on the strangely structured landscapes within Gale Crater.

On Mars, wind rules. Wind has been shaping the Red Planet’s landscapes for billions of years and continues to do so today. Studies using both a NASA orbiter and a rover reveal its effects on scales grand to tiny on the strangely structured landscapes within Gale Crater.

NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover (http://www.nasa.gov/curiosity), on the lower slope of Mount Sharp—a layered mountain inside the crater—has begun a second campaign of investigating active sand dunes on the mountain’s northwestern flank. The rover also has been observing whirlwinds carrying dust and checking how far the wind moves grains of sand in a single day’s time.

Gale Crater observations by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter have confirmed long-term patterns and rates of wind erosion that help explain the oddity of having a layered mountain in the middle of an impact crater.

“The orbiter perspective gives us the bigger picture — on all sides of Mount Sharp and the regional context for Gale Crater. We combine that with the local detail and ground-truth we get from the rover,” said Mackenzie Day of the University of Texas, Austin, lead author of a research report in the journal Icarus about wind’s dominant role at Gale.

The combined observations show that wind patterns in the crater today differ from when winds from the north removed the material that once filled the space between Mount Sharp and the crater rim. Now, Mount Sharp itself has become a major factor in determining local wind directions. Wind shaped the mountain; now the mountain shapes the wind.

The Martian atmosphere is about a hundred times thinner than Earth’s, so winds on Mars exert much less force than winds on Earth. Time is the factor that makes Martian winds so dominant in shaping the landscape. Most forces that shape Earth’s landscapes—water that erodes and moves sediments, tectonic activity that builds mountains and recycles the planet’s crust, active volcanism—haven’t influenced Mars much for billions of years. Sand transported by wind, even if infrequent, can whittle away Martian landscapes over that much time.

Gale Crater was born when the impact of an asteroid or comet more than 3.6 billion years ago excavated a basin nearly 100 miles wide. Sediments including rocks, sand and silt later filled the basin, some delivered by rivers that flowed in from higher ground surrounding Gale. Curiosity has found evidence of that wet era from more than 3 billion years ago. A turning point in Gale’s history—when net accumulation of sediments flipped to net removal by wind erosion—may have coincided with a key turning point in the planet’s climate as Mars became drier, Day noted.

Other new research, using Curiosity, focuses on modern wind activity in Gale.

The rover this month is investigating a type of sand dune that differs in shape from dunes the mission investigated in late 2015 and early 2016. Crescent-shaped dunes were the feature of the earlier campaign—the first ever up-close study of active sand dunes anywhere other than Earth. The mission’s second dune campaign is at a group of ribbon-shaped linear dunes.

Meanwhile, whirlwinds called “dust devils” have been recorded moving across terrain in the crater, in sequences of afternoon images taken several seconds apart.

Be the first to comment