On its way to higher layers of the mountain where it is investigating how Mars’ environment changed billions of years ago, NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover will take advantage of a chance to study some modern Martian activity at mobile sand dunes.

On its way to higher layers of the mountain where it is investigating how Mars’ environment changed billions of years ago, NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover will take advantage of a chance to study some modern Martian activity at mobile sand dunes.

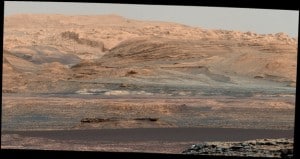

In the next few days, the rover will get its first close-up look at these dark dunes, called the “Bagnold Dunes,” which skirt the northwestern flank of Mount Sharp. No Mars rover has previously visited a sand dune, as opposed to smaller sand ripples or drifts. One dune Curiosity will investigate is as tall as a two-story building and as broad as a football field. The Bagnold Dunes are active: Images from orbit indicate some of them are migrating as much as about 3 feet per Earth year. No active dunes have been visited anywhere in the solar system besides Earth.

“We’ve planned investigations that will not only tell us about modern dune activity on Mars but will also help us interpret the composition of sandstone layers made from dunes that turned into rock long ago,” said Bethany Ehlmann ofCaltech and JPL..

As of Nov. 16, Curiosity has about 200 yards remaining to drive before reaching “Dune 1.” The rover is already monitoring the area’s wind direction and speed each day and taking progressively closer images, as part of the dune research campaign. At the dune, it will use its scoop to collect samples for the rover’s internal laboratory instruments, and it will use a wheel to scuff into the dune for comparison of the surface to the interior.

What distinguishes actual dunes from windblown ripples of sand or dust, like those found at several sites visited previously by Mars rovers, is that dunes form a downwind face steep enough for sand to slide down. The effect of wind on motion of individual particles in dunes has been studied extensively on Earth, a field pioneered by British military engineer Ralph Bagnold (1896-1990). Curiosity’s campaign at the Martian dune field informally named for him will be the first in-place study of dune activity on a planet with lower gravity and less atmosphere.

Observations of the Bagnold Dunes with the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter indicate that mineral composition is not evenly distributed in the dunes. The same orbiter’s High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment has documented movement of Bagnold Dunes.

“We will use Curiosity to learn whether the wind is actually sorting the minerals in the dunes by how the wind transports particles of different grain size,” Ehlmann said.

Ehlmann and Nathan Bridges of the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, Maryland, lead the Curiosity team’s planning for the dune campaign.

“These dunes have a different texture from dunes on Earth,” Bridges said. “The ripples on them are much larger than ripples on top of dunes on Earth, and we don’t know why. We have models based on the lower air pressure. It takes a higher wind speed to get a particle moving. But now we’ll have the first opportunity to make detailed observations.”

THE KELSO DUNES in California’s Mojave Desert are a good example of  somewhat similar dunes on Earth. These dunes, covering 45 square miles near the town of Baker, are called “booming” or “singing” dunes because of the low-pitched resonant noise they produce—especially when someone slides down their steep face. Do the Bagnold Dunes on Mars also boom, when slid down? That’s something for an expedition of human “Martians” to check out, some day.

somewhat similar dunes on Earth. These dunes, covering 45 square miles near the town of Baker, are called “booming” or “singing” dunes because of the low-pitched resonant noise they produce—especially when someone slides down their steep face. Do the Bagnold Dunes on Mars also boom, when slid down? That’s something for an expedition of human “Martians” to check out, some day.

Be the first to comment