If a lot of us feel baffled by simply how to survive the next 24 hours, astronomers are taking a longer view—way out to the year 2028.

If a lot of us feel baffled by simply how to survive the next 24 hours, astronomers are taking a longer view—way out to the year 2028.

That’s when the European Space Agency (ESA) plans to launch the Athena orbiting X-ray Observatory as its second ‘large-class’ science mission in the 21st century. Athena will be the largest X-ray telescope ever built, with a 120-inch diameter X-ray mirror.

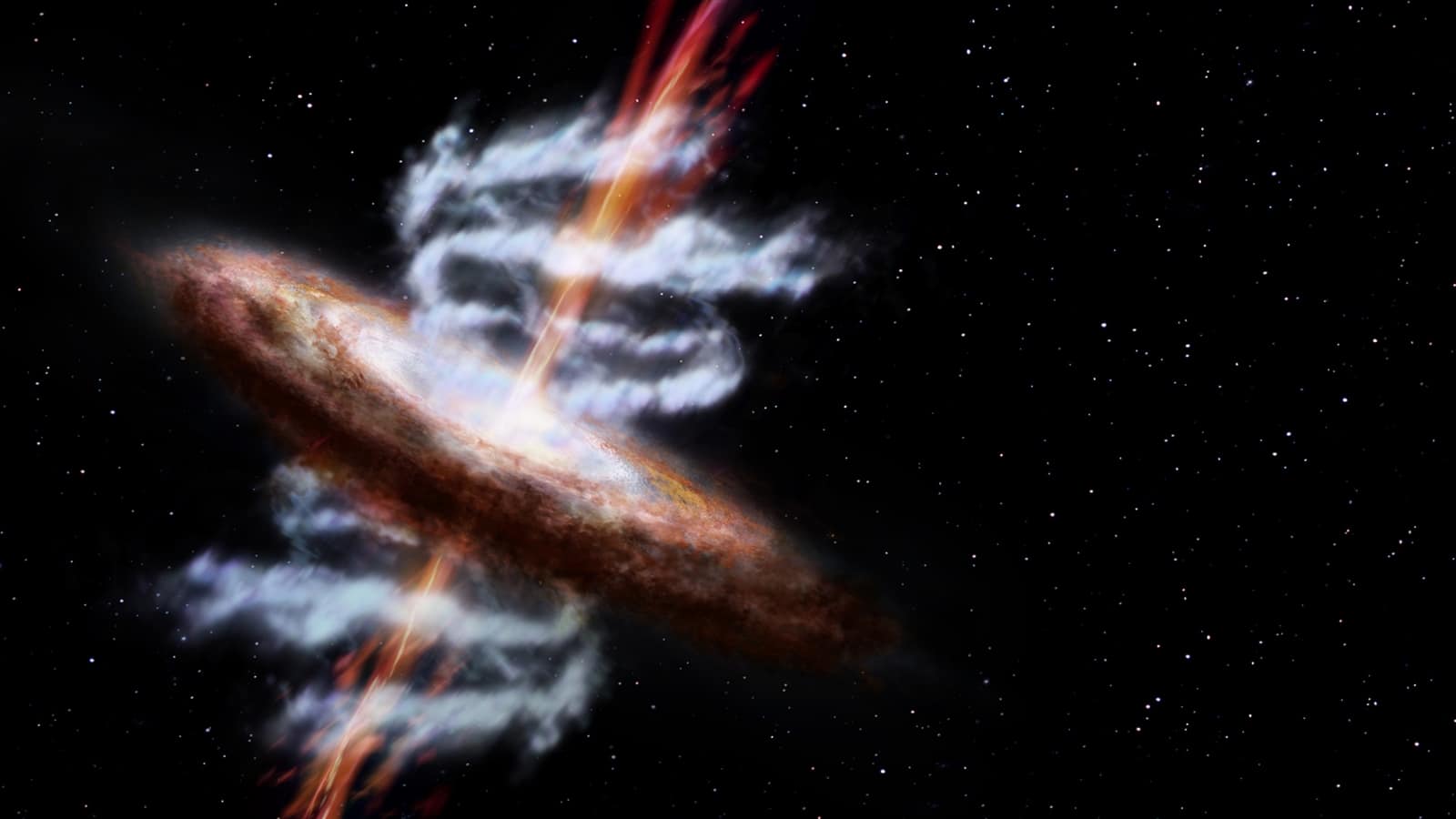

It will observe the X-ray emission from material swallowed by black holes just before it disappears, providing vital information about the extreme gravitational environment around the black hole and the spin of the block hole itself. This will allow for a greater understanding of how black holes grow and the vital role they play in the formation and evolution of the universe.

Observing the universe’s radiation at the extreme short-wave end of the electromagnetic spectrum, ESA’s Athena X-ray Observatory will have capabilities matching NASA’s James Webb Telescope, which is designed to detect near-infrared light at the long-wave end of the visible spectrum. Between them, these space telescopes will vastly improve our ability to learn about two kinds of objects undreamed of just a few decades ago—black holes and exoplanets.

ARCHAEO-ASTRONOMY STEPS OUT FROM SHADOWS OF THE PAST

While most astronomers may be looking toward outer space and the far future, others are  turning their gaze to the distant past. This week, a developing field of research that merges astronomical techniques with the study of ancient man-made features and the surrounding landscapes is being highlighted at the National Astronomy Meeting (NAM) 2014 in Portsmouth, UK. From the “Crystal Pathway” that links stone circles on Cornwall’s Bodmin Moor to star-aligned megaliths in central Portugal, archaeo-astronomers are finding evidence that Neolithic and Bronze Age people were acute observers of the Sun, as well as the Moon and stars, and that they embedded astronomical references within their local landscapes.

turning their gaze to the distant past. This week, a developing field of research that merges astronomical techniques with the study of ancient man-made features and the surrounding landscapes is being highlighted at the National Astronomy Meeting (NAM) 2014 in Portsmouth, UK. From the “Crystal Pathway” that links stone circles on Cornwall’s Bodmin Moor to star-aligned megaliths in central Portugal, archaeo-astronomers are finding evidence that Neolithic and Bronze Age people were acute observers of the Sun, as well as the Moon and stars, and that they embedded astronomical references within their local landscapes.

“There’s more to archaeo-astronomy than Stonehenge,” says Dr. Daniel Brown of Nottingham Trent University, who will present updates on his work on the 4,000-year-old astronomically aligned standing stone at Gardom’s Edge in the UK’s Peak District. “Modern archaeo-astronomy encompasses many other research areas such as anthropology and ethno-astronomy.”

In response to this more cross-fertilized approach, some researchers are proposing to rename the field “skyscape archaeology.” Dr. Fabio Silva, co-editor of the recently established Journal for Skyscape Archaeology, says, “We have much to gain if the fields of astronomy and archaeology come together to a fuller and more balanced understanding of European megaliths and the societies that built them.

Silva’s studies of European megaliths focus on 6,000-year-old winter occupation sites and megalithic structures in the Mondego Valley in central Portugal. He has found that the entrance corridors of all passage graves in a given necropolis are aligned with the seasonal rising over nearby mountains of the star Aldebaran, the brightest star of Taurus. This link between the appearance of the star in springtime and the mountains where the dolmen builders would have spent their summers has echoes in local folklore about how the Serra da Estrela or ‘Mountain Range of the Star’ received its name from a Mondego Valley shepherd and his dog following a star.

Brian Sheen and Gary Cutts of the Roseland Observatory have worked together with Jacky Nowakowski, of Cornwall Council’s Historic Environment Service, to explore an important Bronze Age astro-landscape extending over several square miles on Bodmin Moor in Cornwall. At its heart lie Britain’s only triple stone circles, The Hurlers, of which two are linked by the 4,000-year-old granite pavement, dubbed the Crystal Pathway. The team has confirmed that Bronze Age inhabitants used a calendar controlled by the movements of the Sun. The four cardinal points are marked together with the solstices and equinoxes.

Be the first to comment