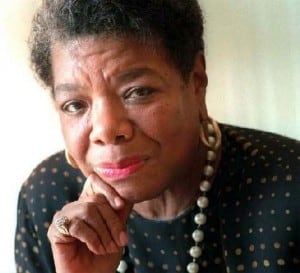

When I hear that one of my heroes has died, I feel sad for a moment. Then I think of how grateful I am to have had them, to have been inspired by their actions, their deeds, their words. Maya Angelou made a tremendous difference for me.

When I hear that one of my heroes has died, I feel sad for a moment. Then I think of how grateful I am to have had them, to have been inspired by their actions, their deeds, their words. Maya Angelou made a tremendous difference for me.

I read “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” when I was a freshman in high school. That she was so candid and so frank about her ordeal won my admiration. That she overcame the pain meant everything to me. If she could do it, then it could be done.

I was instantly drawn into the book because of the trip to Stamps with her brother Bailey. A few years earlier I taken a trip to Chicago that was almost as haphazard. While I did not have a tag on my collar, my sister and I were put on a plane with our grandmother. To any outward glance, it would seem that she was in charge of us, but we had been drafted to take her. She had such Alzheimer’s (before anyone knew what Alzheimer’s was,) she could not even remember our names. The trip from Newark to O’Hare only took one day, but at the end of it, I was feeling like a very grown-up 10 year old.

Reading about Maya and Bailey getting off the train in Stamps, I instantly had a new sister.

Many years later, when I was working as the assistant manager of the student bookstore at Mount St. Mary’s College, it was announced that Angelou would be the keynote speaker for Career Day, The Mount is an all-women’s college, run by the Carondelet Sisters of St. Joseph, a teaching order specializing in nursing. Our campus was filled with young women of color, perched high on hill in Brentwood overlooking the city all the way down to the bay. I used to joke that it was like watching teenagers go through med school; the first week of school was our only truly busy moment, with girls buying stacks of medical texts almost as high as they were tall.

Career Day meant we had another bookselling moment to prep for, and I ordered boxes of “Caged Bird” along with her other volumes of autobiography, and a collection of her poetry as well. We put up posters that she would be signing books after the reception. The students were almost crazed with anticipation. It was only a few of the older nuns who had not heard of her and read her work.

When the day arrived, everyone and everything was polished to a gleam. We met in the multi-purpose room downstairs from the store, the room packed with dark haired women and nuns in dressed in black. There were moms, too, and plenty of sisters, aunts and grandmothers filling the chairs. When Angelou arrived, there was a spontaneous ovation.

She spoke to the girls in that richly cadenced voice about the life they might chose to have by keeping their ideals high and their talents sharp. They drank in every word like dusty roses in a rain shower. I stood by the back door, ready to make a dash for it when the crowd would head over to the bookstore for the signing.

“And in closing,” Angelou said, “I would like all of us to join together in singing the Black National Anthem, Life Ev’ry Voice and Sing, by the wonderful poet, James Weldon Johnson. ” An elderly nun standing near me said “I’ve never heard of such a thing.” I said “I’ve heard of it, I just can’t sing it.” I knew James Weldon Johnson on paper, but I’d no idea there was a melody for “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing.”

The girls knew it; they knew it by heart. The rafters rang. It resounded loud as the rolling sea.

There was sisterhood, and then, there was Sisterhood.

Silently I walked my working-girl shoes out the door and back up to the bookstore to check the set-up and make sure we were ready. While there was coffee and cake downstairs, I slipped the dust jacket into the title page on a few dozen volumes so they would open easily and be ready to sign. I cracked open a pack of black fine-point Sharpie markers and set them into an elegant coffee cup next to the chair.

I waited.

When Angelou came in, escorted by the administrators, I could see that they were all as starstruck as the girls. Angelou was kind, and cool. She sat and asked me to take her coffee “somewhere that it won’t spill” and I found a shelf near my desk.

She was warm but professional, asking about dedications, graciously signing as many copies as each fan presented her with. I handed her book after book after book. More than an hour later, when the line had ended and we put our “Back Soon” sign on the door and locked up, I asked if she still wanted her coffee as it was certainly cold. Cold was fine, she said, all she wanted at the moment was wet. I went back to my desk and she followed me.

Finishing her coffee, she thanked me for my help. and I thanked her for all her kindness to our students and their families. She asked “Are you a graduate of this school?” and I offered that I wasn’t. “Where did you graduate? ”

“Um, well, I haven’t. I just like working in bookstores.” I felt as self-conscious over the ‘um’ as I did over the lack of degree. Here was a woman who had saved her life by learning to speak clearly, and I was stumbling over excuses. She gestured out the window at the magnificent view and said “That world out there needs you. It may feel very safe to live on an island of women, but safe does not win the day. Don’t stay here too much longer, you are at risk of getting too comfortable to leave.” Her driver pulled up in front of the store and came around to open the door for her. The nuns were waiting to offer their thanks.

There is a quotation from Angelou, “I don’t believe the accident of birth makes people brothers and sisters, it makes them siblings. Sisterhood and brotherhood is a condition people have to work at.”

After I left that bookstore, I published my poetry, and my journalism, and my essays. I also found a few sisters and brothers in the world.

When I heard that Maya Angelou died, I exclaimed out loud. But my distress over her death quickly softened as I read and heard so many cherishing her work, calling her a poet. That we are spending so much emotion mourning for her speaks volumes.

Sisterhood is powerful, it just takes work.

Be the first to comment