Polish Roots –My paternal grandparents were born in Poland. As a child, I tried to keep this a secret. “Polish jokes” abounded; I did not realize then that Jewish comedians themselves perpetrated these jokes by doing “cover versions” of typical “us-them” jokes from pre-war Poland, where Jews were marginalized even before the Nazis swept through and destroyed the people, the culture and the communities. During my childhood and formative years, Poland was “behind the iron curtain,” and off-limits to “The West.”

Polish Roots –My paternal grandparents were born in Poland. As a child, I tried to keep this a secret. “Polish jokes” abounded; I did not realize then that Jewish comedians themselves perpetrated these jokes by doing “cover versions” of typical “us-them” jokes from pre-war Poland, where Jews were marginalized even before the Nazis swept through and destroyed the people, the culture and the communities. During my childhood and formative years, Poland was “behind the iron curtain,” and off-limits to “The West.”

My mother’s parents claimed to be “Yankees” (third-generation American) and to have come from “Russia or somewhere.” To this day, the family doesn’t even know what town, but I do know that they left at a time when “Poland” did not exist as a country, politically. In any case, when I grew up in the 60’s and 70’s, you wouldn’t have considered Poland to be a tourist destination.

Still, I was exposed to my Polish roots from an early age. My father’s parents would say stuff in Polish. Instead of “good night,” my father would say, “guvnish” to us, which may sound like “good night,” but actually means “shit.” My grandma would sing Polish songs to herself, and rhapsodize about how beautiful the rivers and forests were where she grew up, in Czestochowa and, later, Lodz. Telling stories about her childhood, she’d stop mid-story, heave a sigh, and begin to sob silent tears. All but one sister who also emigrated to the U.S. were murdered during The Holocaust.

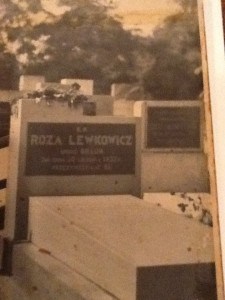

Only photographs and scattered memories remain. By the time my father died in 2009, the Berlin Wall had fallen, the internet could take you anywhere, and I’d managed to research some information about where and how my family had lived in Poland before the war. In my father’s personal effects, two photographs of a couple of stylishly dressed people standing by some gravestones spoke to me. I decided to take these pictures, and my two sons, on a spring vacation trip to Poland in 2011.

Another impetus of the trip was that I’d found out that the Chief Rabbi of Poland, based in Warsaw, was my former Rabbi from the Tokyo Jewish Community Center in the 1980’s. I contacted him via e-mail, and he encouraged us to come, assisted us on itinerary choices, and welcomed us at his synagogue: the only remaining active synagogue in Warsaw, which, then and now, is a world-class metropolis with a population of Jews before WWII constituting a larger percentage than Los Angeles’ Latino community today.

An event that occurred on this trip rates to this day on my top five list of travel experiences ever: I found those graves pictured in the photos!

After visiting Warsaw, Lublin and Bialystok, for general historical perspective, we arrived for a short weekend in Lodz, the first of three cities my research pointed us to for our “own” family history. We visited the Lodz Jewish cemetery that morning, because it was the major Jewish “tourist” attraction of the city, and because I had a sense that some relatives of ours might have been buried there. However, it wasn’t until three hours before our train departure later the same day that I received a call from Rabbi Schudrich, informing me that he’d arranged for the leader of the Lodz Jewish community to see us.

We rushed to meet him. I unfurled a web download I’d brought from my home computer, which showed a partial family tree that had been compiled by researchers of the Czestochowa (a different city, where my grandmother was said to have been born) Jewish community. The names in the family tree were in Yiddish (thankfully, transliterated into Latin alphabet letters). I also had the two photographs in hand, but was told that they “couldn’t be used,” which I didn’t understand, at first.

I learned that the photos wouldn’t be helpful, because the maze of gravestones were inscribed with people’s Polish names, whereas the cemetery register listed only the Yiddish names of the interned, along with a number and letter for the burial site. I was given a slip of paper with some numbers on it, and told, if we wanted to see the graves, we could make it just before closing time by cabbing it back to the cemetery, on our way to the train station.

We hailed a cab, filled it with our luggage, and then I had to channel back my college German (settled on as our only common language) to instruct the cabbie to take us to the cemetery, wait for us, and then proceed to the train station.

A $100 cab ride later, the cemetery proprietor had cross-checked his log, and led us, through underbrush and ivy, to both gravesites: my great-grandfather’s, the headstone of which had been destroyed over the years since 1926 (see photo) and my great-grandmother’s (1935) which, although in tact, had been toppled over (see photo #3). The unfinished business I said I have with Poland in my first article relates to this: I plan to find the means to restore the gravestones, and try to do more research about how and where my grandmother’s sisters lived and how their families perished in the Holocaust.

Separate from this significant event, but on the same trip, it was at Majdanek Concentration Camp, just outside of Lublin, that we decided to go to Israel the following spring break. More about this in my next post.

Enjoying your articles!

Love reading your articles! Can’t wait for the next one!

Can’t wait for the rest of the story. Guvnish!