The forecast for today is “Smoke” again and my throat is sore and scratchy. It is not nearly so bad here as it is in the northern half of the state, and the two states further north still, where shifting winds have changed the sky from an ominous Martian red to a pink faux-sunset that never actually sets. Still, the sky above us shifts from a dingy grey to pale pink and despite the fact that there is absolutely 0% chance of rain, we never see blue overhead. In April we had the best air quality on record and over the last week we have shifted to having the worst air quality on the planet.

Catastrophic climate change is here. Not only is this side of the continent burning, but there are equally devastating wildfires burning through Argentina, Brazil, and Siberia right now.

Not only are there five named cyclonic storm systems in the Atlantic (for the second time ever –– the first was in 1971, a season which ended in November with Tropical Storm Laura –– now Hurricane Sally is set to make landfall somewhere along the Gulf of Mexico), but Iowa is still trying to figure out how to recover from the derecho that hit a month ago and if you don’t know what a “derecho” is, you’re not alone. The current flows and the weather they form define some of the most complex mathematics known to mankind, but to wildly oversimplify, a derecho is basically the equivalent of a hurricane that has formed entirely over land. It’s not at all easy for such a forceful storm to form over land, and so derechos are exceedingly rare.

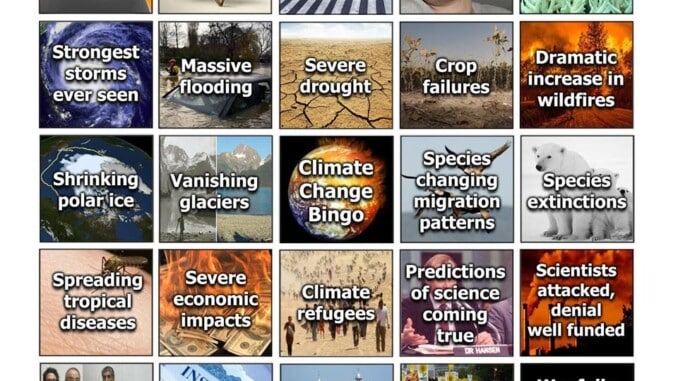

If anyone had bothered to make a climate disaster bingo card this year, they would not only have bingo, but would likely have bingo several times over. That’s not even counting the pandemic, though it is as much a symptom of our planet’s mind-bogglingly complex and delicately balanced system going haywire as any other.

These are not random convergences or fluctuations in the Earth’s natural cycle. The polar vortices and “Snowpocalypses” of the past few years are not evidence that “the science isn’t really clear”. They are as much a part of this catastrophe as the fires, droughts, storms, and floods. Much like a spinning top begins to wobble before it falls over and stops spinning, the weather patterns oscillate between greater extremes before finding a new, warmer equilibrium. Our climate is becoming unsurvivably unstable and we humans must confront that we have done this ourselves.

While the US president lies about the impact of global warming, just as he lied about the threat of the pandemic, just has he has lied about every single great and small thing his administration has touched, while he has set our entire world back years, if not decades with unprecedented deregulation of oil drilling and fossil fuel consumption, while he pulled our nation from the Paris Climate Accords, the problem was so vast, so complex, requiring a unification of humanity the likes of which the world had never literally never seen, not even in the midst of pandemic, that it may have been unsolvable long before he took office.

It was probably five years ago, while Littlest was still well and truly little, that we had a frank discussion about our planet and what our future looked like. It had only been a year or so before that she sat me down on the edge of the bed and said, “Can you please just tell me the truth about Santa Claus?” and now she started with, “I worry about what the world will be like when I grow up. I worry about global warming and people not having a place to live and people starving and suffering and dying and I don’t know what will happen and I don’t know what to do.”

She was seven, eight years old. The year I turned eight, I spent the summer tying floral ribbons to the seat belts and hounding any adult in the car to buckle up until it was a habit for all of us. I felt proud of myself for helping to save lives and to make the world a better place. She was staring down a problem where the smartest minds of a generation hadn’t penetrated the mathematics, the most accomplished financiers had not vaulted the economic hurdles, and even the unprecedented international efforts rested on diplomatically shaky ground.

I took a deep breath. She’d asked difficult questions before and she would ask difficult questions again. “I can tell you what will probably happen. You won’t like it.”

“Yes, people will starve, people will suffer, people will lose their homes, people will die. What is particularly cruel is which people will endure the most devastating losses. They will be poor people in poor countries, people who never consumed a hundredth of what you or I have in our lives, people who in no way deserved to have horrible things happen to them.”

“The rich people –– and by ‘rich’ I do not mean Daddy Warbucks, but people like us. We don’t feel rich but we live comfortable lives and we have resources we can draw on in an emergency –– the rich people, when they are hit with catastrophe, will pick up and move to places that are still liveable and they will be able to. They will have the money to pack up their possessions, to pay for a home in a place where temperatures are still mild and living things still grow. They will go to all the nice places, the lovely places, and they will fill them up while they leave the people who have no ability to escape behind to whatever inevitability the planet brings.”

“You are incredibly privileged. You were born into a family that has wealth, has the ability to flee from disaster and to start a new life someplace where life is worth living. You are also deeply kind, you think about and care about others and the guilt that your freedom brings will be crushing as the world sinks into greater turmoil.”

“I would never discourage you from being a climate scientist and spending your life studying this problem and trying to figure out how to make it better, but it is a very large, very complex problem, bigger than anyone one person can solve. You could spend your whole life on this problem and only contribute one tiny piece, and that would be okay…would be wonderful, really, but it might feel very discouraging. There really isn’t a bigger, tougher problem in the world than global warming.”

“I can suggest only one other thing that might help, though it will always feel inadequate. Understand what privilege you have, what resources you can access that many others can’t, and be ready to use that privilege to help and to lift up as many others who lack what you are blessed with as you can. Save as many as you can save, extend the freedom you enjoy to whoever you can reach, and do not let yourself only look out for your own. It is not wrong to be privileged, but also, it is not right to let another suffer from want when you have all that you need and more.”

I knew our equilibrium was already wobbly, that collapse was coming faster than any of us thought, but I did not expect that the moment she dreaded would be upon us while she was still a child. Climate migration is no longer an abstract concept in academic papers –– it is here among those who are displaced in the short and long term by the ravages of fire and smoke and storm and flood, by famine, and by the wars and civil unrest that “natural” disasters inevitably bring. It is the refugees turned away from distant shores and held in detention centers within our borders, and the “displaced” who wander our streets with a safe and secure home beyond their reach.

The deaths are here too, though we squabble over the causes rather than recognizing the staggering scale of the damage we have done. Hurricanes tear through a region and we have no capacity to calculate how many would still be alive had we not thrown our atmosphere into chaos. We count those who are consumed by flames of wildfire but not those who are choked over days, weeks, months, years of unbreathable air. Crops fail, people starve, more unfortunate deaths we tell ourselves we could have done nothing to prevent. And then there are the pandemic deaths and we try to tell ourselves that these people would have died anyway because we cannot face that our actions tore families apart needlessly.

Five years later, the problem remains as intractable as ever. The greatest minds of a generation are, alone, unsupported, still woefully inadequate to the task. The only solution remains absolutely unprecedented worldwide unity. Humanity still has an opportunity, but if the pandemic was a test of our species’ ability to unite for our common good, we have failed badly. And so long as we cannot put one another’s needs before our own even in the short term, we will, in the long term, be counting our dead not in the millions, but in the billions. This will be the world in which our children become grown-ups. This will be the world that we will live to see. This is the world ten years, five years, two years out.

Our youngest is still a long way from grown up, but she wants to be a zoologist. She wants to study bats. Bats are far more than a disease vector for humans. Bats help keep the insect population in balance. Bats are pollinators. Bats help plants grow and plants capture and sequester carbon and help cool our overheating planet. Bats are one tiny piece of the incomprehensibly complex system and a lifetime’s work to support and preserve. She’s still worried, still frightened, but she still wants to reach out with that one tiny piece, to join it together with the several billion others…to save bats, save people, save our world.

#scenesfromquarantine

Tanya Klowden

Be the first to comment