The call everyone was waiting for is in. NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft phoned home just before 9 p.m. EDT Tuesday, July 14, to tell the mission team and the world it had accomplished the historic first-ever flyby of Pluto.

The call everyone was waiting for is in. NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft phoned home just before 9 p.m. EDT Tuesday, July 14, to tell the mission team and the world it had accomplished the historic first-ever flyby of Pluto.

“I know today we’ve inspired a whole new generation of explorers with this great success, and we look forward to the discoveries yet to come,” NASA Administrator Charles Bolden said. “This is a historic win for science and for exploration. We’ve truly, once again raised the bar of human potential.”

The preprogrammed “phone call”—a 15-minute series of status messages beamed back to mission operations at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland through NASA’s Deep Space Network—ended a very suspenseful 21-hour waiting period. New Horizons had been instructed to spend the day gathering the maximum amount of data, and not communicating with Earth until it was beyond the Pluto system.

Pluto is the first Kuiper Belt object visited by a mission from Earth. New Horizons will  continue on its adventure deeper into the Kuiper Belt, where thousands of objects hold frozen clues as to how the solar system formed.

continue on its adventure deeper into the Kuiper Belt, where thousands of objects hold frozen clues as to how the solar system formed.

New Horizons is collecting so much data it will take 16 months to send it all back to Earth.

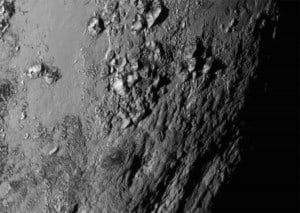

PLUTO’S ICY MOUNTAINS. Close-up images of a region near Pluto’s equator reveal a giant surprise: a range of youthful mountains rising as high as 11,000 feet above the surface of the icy body.

The mountains likely formed no more than 100 million years ago—mere youngsters relative to the 4.56-billion-year age of the solar system—and may still be in the process of building, says Jeff Moore of New Horizons’ Geology, Geophysics and Imaging Team (GGI). That suggests the close-up region, which covers less than one percent of Pluto’s surface, may still be geologically active today.

Moore and his colleagues base the youthful age estimate on the lack of craters in this scene. Like the rest of Pluto, this region would presumably have been pummeled by space debris for billions of years and would have once been heavily cratered—unless recent activity had given the region a facelift, erasing those pockmarks.

“This is one of the youngest surfaces we’ve ever seen in the solar system,” says Moore.

Unlike the icy moons of giant planets, Pluto cannot be heated by gravitational interactions with a much larger planetary body. Some other process must be generating the mountainous landscape.

Unlike the icy moons of giant planets, Pluto cannot be heated by gravitational interactions with a much larger planetary body. Some other process must be generating the mountainous landscape.

The mountains are probably composed of Pluto’s water-ice “bedrock.”

Although methane and nitrogen ice covers much of the surface of Pluto, these materials are not strong enough to build the mountains. Instead, a stiffer material, most likely water-ice, created the peaks. “At Pluto’s temperatures, water-ice behaves more like rock,” said deputy GGI lead Bill McKinnon of Washington University, St. Louis.

The close-up image was taken about 1.5 hours before New Horizons closest approach to Pluto, when the craft was 478,000 miles from the surface of the planet. The image easily resolves structures smaller than a mile across.

NASA TV schedules, satellite coordinates, and links to streaming video:

www.nasa.gov/nasatv

The public can follow the path of the spacecraft in coming days in real time with a visualization of the actual trajectory data, using NASA’s online Eyes on Pluto (eyes.nasa.gov/pluto).

More information on the New Horizons mission:

www.nasa.gov/newhorizons

solarsystem.nasa.gov/planets/plutotoolkit.cfm

Be the first to comment