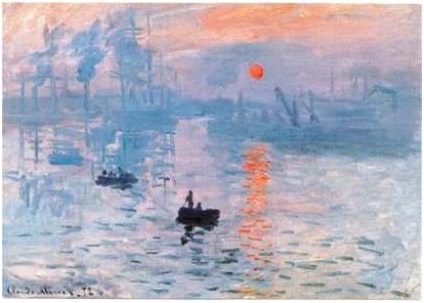

The Impressionist movement of the late 19th century takes its name from French artist Claude Monet’s moody, dreamlike painting “Impression, Soleil Levant” (“Impression, Sunrise”). Now, Texas State University astronomer and physics professor Donald Olson has applied his distinctive brand of celestial sleuthing to Monet’s masterpiece, uncovering new details about the painting’s origins and resolving some long-standing controversies over what the canvas depicts and when it was painted.

The Impressionist movement of the late 19th century takes its name from French artist Claude Monet’s moody, dreamlike painting “Impression, Soleil Levant” (“Impression, Sunrise”). Now, Texas State University astronomer and physics professor Donald Olson has applied his distinctive brand of celestial sleuthing to Monet’s masterpiece, uncovering new details about the painting’s origins and resolving some long-standing controversies over what the canvas depicts and when it was painted.

Olson’s findings are published by the Musée Marmottan Monet of Paris, France, in “Monet’s ‘Impression Sunrise’: The Biography of a Painting,” the catalog of the museum’s major Monet exhibition running Sept. 18, 2014, to Jan. 18, 2015.

A ROOM WITH A VIEW

“For several other Monet paintings from Le Havre, we can be certain that the artist depicted the topography of the port accurately,” Olson said. “’Impression, Soleil Levant’ likewise appears to be an accurate representation of a sparkling glitter path extending across the waters of the harbor, beneath a solar disk seen through the mist accompanying a late fall or winter sunrise.”

Monet dated his signature with a “72” on the painting, but some subsequent catalogs dismiss that number and date the painting to 1873, assuming that Monet had worked in Le Havre during the spring of that year. The hazy nature of the image further confused the issue, with various sources disagreeing regarding the season of the year depicted and the direction of Monet’s view. Several influential art historians even insisted that the canvas depicted a sunset, not a sunrise. Monet himself helped to resolve some of the uncertainty in an interview from 1898:

“I had submitted something done in Le Havre, from my window, the Sun in the mist and a few masts of ships in the foreground…. They asked me the title for the catalog; it could not really pass for a view of Le Havre, so I replied: ‘Put Impression.’ From that came ‘Impressionism,’ and the jokes proliferated.”

Olson began his work by consulting 19th-century maps and collecting more than 400 vintage photographs of Le Havre. One especially clear and detailed photograph made it possible to identify the precise hotel room from which Monet worked. Olson confirmed the view from the room to the southeast matched that of the painting and subsequently calculated the Sun’s position over the harbor—roughly 20 to 30 minutes after sunrise. To further narrow the possible dates, Olson then looked at the tides. Since the large sailing ships could only enter and exit the shallow outer harbor during a few hours near of high tide, he used computer algorithms to calculate the tides of that era. The result was 19 possible dates in late January and mid-November of 1872 and 1873 when the Sun and tides corresponded with the painting.

WHAT’S THE WEATHER LIKE?

Weather reports were the next clue in Olson’s detective work.

“Meteorological observations allow us to reject some of the proposed dates, because of the bad weather common on the Normandy coast during the late fall and winter months,” Olson explained. “Weather archives also can identify some dates when the sky conditions match the appearance in ‘Impression, Soleil Levant.’”

Six dates remained after eliminating those with stormy, rainy or windy weather and heavy seas. To narrow the field even further, Olson examined the smoke columns rising over the harbor on the left side of the painting. The smoke appears to be blowing to the right, which would indicate a wind from the east. Two remaining dates record an east wind: Nov. 13, 1872, and Jan. 25, 1873.

An essay by art historian Géraldine Lefebvre in the exhibition catalog gives reasons for preferring the year 1872—matching the original date “72” painted by Monet next to his signature on the canvas—and the combined analysis points to Nov. 13, 1872, at 7:35 a.m. local mean time, as the definitive date and time when Monet created “Impression, Soleil Levant.”

Be the first to comment