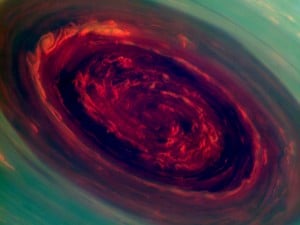

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has provided scientists the first close-up, visible-light views of a behemoth hurricane swirling around Saturn’s north pole.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has provided scientists the first close-up, visible-light views of a behemoth hurricane swirling around Saturn’s north pole.

In high-resolution pictures and video, scientists could see that the hurricane’s eye is about 1,250 miles wide—20 times larger than the average hurricane eye on Earth. Thin, bright clouds at the outer edge of the hurricane are traveling 330 miles per hour (150 meters per second). The hurricane swirls inside a large, mysterious, six-sided weather pattern known as the hexagon.

“We did a double take when we saw this vortex because it looks so much like a hurricane on Earth,” said Andrew Ingersoll, a Cassini imaging team member at Caltech. “But there it is at Saturn, on a much larger scale, and it is somehow getting by on the small amounts of water vapor in Saturn’s hydrogen atmosphere.”

Scientists will be studying the hurricane to gain insight into hurricanes on Earth, which feed off warm ocean water. Although there is no body of water close to these clouds high in Saturn’s atmosphere, learning how these Saturnian storms use water vapor could tell scientists more about how terrestrial hurricanes are generated and sustained.

Both a terrestrial hurricane and Saturn’s north polar vortex have a central eye with no clouds or very low clouds. Other similar features include high clouds forming an eye wall, other high clouds spiraling around the eye, and a counter-clockwise spin in the northern hemisphere.

A major difference between the hurricanes is that the one on Saturn is much bigger than its counterparts on Earth and spins surprisingly fast. At Saturn, the wind in the eye wall blows more than four times faster than hurricane force winds on Earth. Unlike terrestrial hurricanes, which tend to move, the Saturnian hurricane is locked onto the planet’s north pole. On Earth, hurricanes tend to drift northward because of the forces acting on the fast swirls of wind as the planet rotates. The one on Saturn does not drift and is already as far north as it can be.

“The polar hurricane has nowhere else to go, and that’s likely why it’s stuck at the pole,” said Kunio Sayanagi, a Cassini imaging team associate at Hampton University in Hampton, Va.

Scientists believe the massive storm has been churning for years. When the Cassini spacecraft arrived in the Saturn system in 2004, Saturn’s north pole was dark because the planet was in the middle of its north polar winter. During that time, Cassini’s composite infrared spectrometer and visual and infrared mapping spectrometer detected a great vortex at the north pole, but a visible-light view had to wait for the passing of the planet’s equinox in August 2009. Only then did sunlight begin flooding Saturn’s northern hemisphere. The view required a change in the angle of the spacecraft’s orbits around Saturn—a difficult and fuel-consuming maneuver—so it could see the poles.

“Such a stunning and mesmerizing view of the hurricane-like storm at the north pole is only possible because Cassini is on a sportier course, with orbits tilted to loop the spacecraft above and below Saturn’s equatorial plane,” said Scott Edgington, Cassini deputy project scientist at JPL. “You cannot see the polar regions very well from an equatorial orbit. Observing the planet from different vantage points reveals more about the cloud layers that cover the entirety of the planet.”

Be the first to comment