Evidence of Liquid Water on Icy Europa

Evidence of Liquid Water on Icy Europa

Analysis of data from NASA’s Galileo planetary mission has turned up evidence of what appears to be a body of liquid water equal in volume to North America’s Great Lakes beneath the icy surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa.

The Galileo data suggest there is significant exchange between Europa’s icy shell and the ocean beneath. This information could bolster arguments that this moon’s global subsurface ocean represents a potential habitat for life elsewhere in our solar system. The findings are published in the scientific journal Nature.

“The data opens up some compelling possibilities,” said Mary Voytek, director of NASA’s Astrobiology Program at agency headquarters in Washington. “However, scientists worldwide will want to take a close look at this analysis and review the data before we can fully appreciate the implication of these results.”

NASA’s Galileo spacecraft, launched by the space shuttle Atlantis in 1989 to Jupiter, produced numerous discoveries and gave scientists decades of data to analyze. Galileo studied Jupiter, which is the most massive planet in the solar system, and some of its many moons.

One of the most significant discoveries was the inference of a global salt water ocean below the surface of Europa. This ocean is deep enough to cover the whole surface of Europa and contains more liquid water than all of Earth’s oceans combined. However, being far from the Sun, the ocean surface is completely frozen. Most scientists think

this ice crust is tens of miles thick.

“One opinion in the scientific community has been if the ice shell is thick, that’s bad for biology. That might mean the surface isn’t communicating with the underlying ocean,” said Britney Schmidt, lead author of the paper and postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas at Austin. “Now, we see evidence that it’s a thick ice shell that can mix vigorously and new evidence for giant shallow lakes. That could make Europa and its ocean more habitable.”

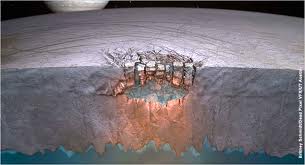

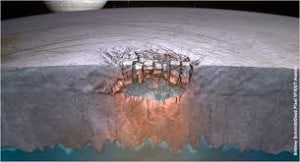

Schmidt and her team focused on Galileo images of two roughly circular, bumpy features on Europa’s surface called chaos terrains. Based on similar processes seen on Earth—on ice shelves and under glaciers overlaying volcanoes—they developed a four-step model to explain how the features form. The model resolves several conflicting observations. Some seemed to suggest the ice shell is thick. Others suggested it is thin.

This recent analysis shows the chaos features on Europa’s surface may be formed by mechanisms that involve significant exchange between the icy shell and the underlying lake. This provides a way to transfer nutrients and energy between the surface and the vast global ocean already inferred to exist below the thick ice shell. This is thought to increase the potential for life there.

Galileo was the first spacecraft to directly measure Jupiter’s atmosphere and conduct long-term observations of the Jovian system. On its way to Jupiter, it also became the first spacecraft to fly by an asteroid and discover the moon of an asteroid. NASA extended the mission three times to take advantage of Galileo’s unique science capabilities, and it was finally put on a collision course into Jupiter’s atmosphere in September 2003 to eliminate any chance of impacting and contaminating Europa.

More information about the Galileo mission:

http://solarsystem.nasa.gov/galileo

http://www.jsg.utexas.edu/news/files/mag_cover_v02.jpg

You can contact Bob Eklund at [email protected], or visit his website at www.bobeklund.com.

Be the first to comment