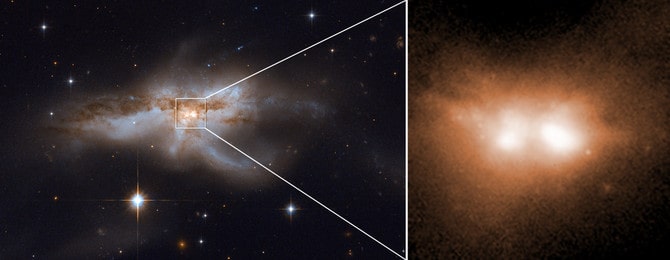

Peering through thick walls of gas and dust surrounding the messy cores of merging galaxies, astronomers are getting their best view yet of close pairs of supermassive black holes as they march toward coalescence into mega black holes.

A team of researchers led by Michael Koss of Eureka Scientific Inc., in Kirkland, Washington, performed the largest survey of the cores of nearby galaxies in near-infrared light, using high-resolution images taken by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (http://www.nasa.gov/hubble) and the W. M. Keck Observatory (http://keckobservatory.org) in Hawaii. The Hubble observations represent over 20 years’ worth of snapshots from its vast archive.

“Seeing the pairs of merging galaxy nuclei associated with these huge black holes so close together was pretty amazing,” Koss said. “In our study, we see two galaxy nuclei right when the images were taken. You can’t argue with it; it’s a very ‘clean’ result, which doesn’t rely on interpretation.”

The images also provide a close-up preview of a phenomenon that must have been more common in the early universe, when galaxy mergers were more frequent. When galaxies collide, their monster black holes can unleash powerful energy in the form of gravitational waves, the kind of ripples in space-time that were just recently detected by ground-breaking experiments.

The new study also offers a preview of what will likely happen in our own cosmic backyard, in several billion years, when our Milky Way combines with the neighboring Andromeda galaxy and their respective central black holes smash together.

“Computer simulations of galaxy smashups show us that black holes grow fastest during the final stages of mergers, near the time when the black holes interact, and that’s what we have found in our survey,” said study team member Laura Blecha of the University of Florida, in Gainesville. “The fact that black holes grow faster and faster as mergers progress tells us galaxy encounters are really important for our understanding of how these objects got to be so monstrously big.”

A galaxy merger is a slow process lasting more than a billion years as two galaxies, under the inexorable pull of gravity, dance toward each other before finally joining together. Simulations reveal that galaxies kick up plenty of gas and dust as they undergo this slow-motion train wreck.

The ejected material often forms a thick curtain around the centers of the coalescing galaxies, shielding them from view in visible light. Some of the material also falls onto the black holes at the cores of the merging galaxies. The black holes grow at a fast clip as they engorge themselves with their cosmic food, and, being messy eaters, they cause the infalling gas to blaze brightly. This speedy growth occurs during the last 10 million to 20 million years of the union. The Hubble and Keck Observatory images captured close-up views of this final stage, when the bulked-up black holes are only about 3,000 light-years apart—a near-embrace in cosmic terms.

The team first searched for visually obscured, active black holes by sifting through 10 years’ worth of X-ray data from the Burst Alert Telescope (BAT) aboard NASA’s Neil Gehrels Swift Telescope, a high-energy space observatory. “Gas falling onto the black holes emits X-rays, and the brightness of the X-rays tells you how quickly the black hole is growing,” Koss explained.

Be the first to comment