After a two-and-a-half-hour descent, the metallic, saucer-shaped spacecraft came to rest with a thud on a dark floodplain covered in cobbles of water ice, in temperatures hundreds of degrees below freezing. The alien probe worked frantically to collect and transmit images and data about its environs—in mere minutes its mothership would drop below the local horizon, cutting off its link to the home world and silencing its voice forever.

After a two-and-a-half-hour descent, the metallic, saucer-shaped spacecraft came to rest with a thud on a dark floodplain covered in cobbles of water ice, in temperatures hundreds of degrees below freezing. The alien probe worked frantically to collect and transmit images and data about its environs—in mere minutes its mothership would drop below the local horizon, cutting off its link to the home world and silencing its voice forever.

Although it may seem the stuff of science fiction, this scene played out 12 years ago on the surface of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. The “aliens” who built the probe were us. This was the triumphant landing of ESA’s Huygens probe.

Huygens, a project of the European Space Agency, traveled to Titan as the companion to NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, and then separated from its mothership on Dec. 24, 2004, for a 20-day coast toward its destiny at Titan.

The probe was named after the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695), who discovered Titan in 1655 using a 50-power refracting telescope of his own design.

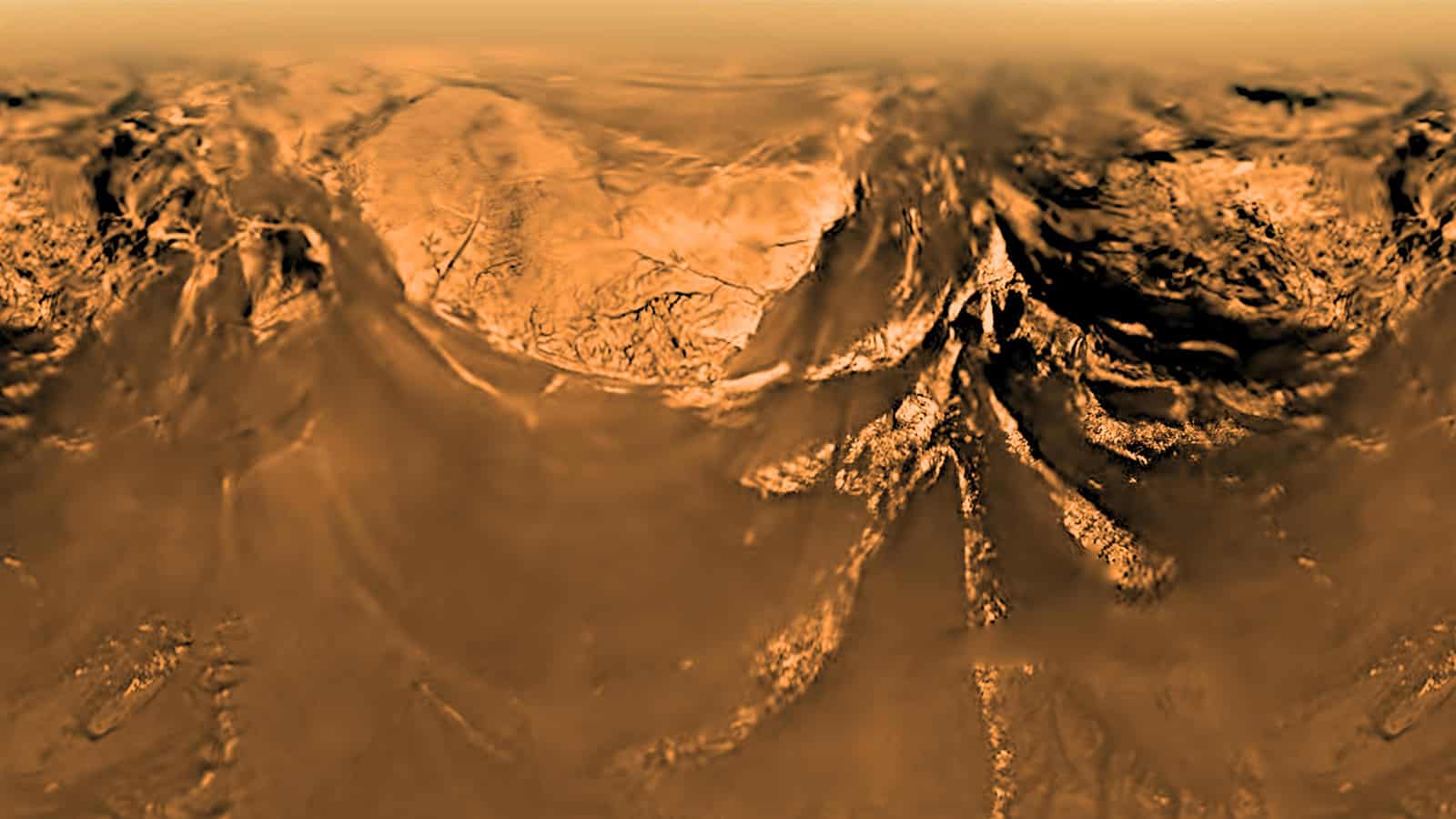

The Huygens probe sampled Titan’s dense, hazy atmosphere as it slowly rotated beneath its parachutes, analyzing the complex organic chemistry and measuring winds. It also took hundreds of images during the descent, revealing bright, rugged highlands that were crosscut by dark drainage channels and steep ravines. The area where the probe touched down was a dark, granular surface, which resembled a dry lakebed.

Today the Huygens probe sits silently on the frigid surface of Titan, its mission concluded mere hours after touchdown, while the Cassini spacecraft continues the exploration of Titan from above as part of its mission to learn more about Saturn and its moons. Now in its dramatic final year, the Cassini spacecraft’s own journey will conclude on September 15, 2017, with a fateful plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere.

As the mission heads into its home stretch, Cassini team members look back fondly on the significance of Huygens:

“The Huygens descent and landing represented a major breakthrough in our exploration of Titan as well as the first soft landing on an outer-planet moon. It completely changed our understanding of this haze-covered ocean world,” notes Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California.

Carolyn Porco, Cassini imaging team lead at Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colorado, adds: “The Huygens images were everything our images from orbit were not. Instead of hazy, sinuous features that we could only guess were streams and drainage channels, here was incontrovertible evidence that at some point in Titan’s history—and perhaps even now—there were flowing liquid hydrocarbons on the surface. Huygens’ images became a Rosetta stone for helping us interpret our subsequent findings on Titan.”

A collection of the Huygens program’s top science findings is available from this ESA website:

http://sci.esa.int/huygens-titan-science-highlights

For more information about NASA’s Cassini program and the Cassini spacecraft, see:

www.nasa.gov/cassini

saturn.jpl.nasa.gov

Be the first to comment